“Allowing children to be surrounded by beauty and immersed in music is my main purpose in creating this art center.” – Paul Chiang

Nurturing a sense of beauty is sometimes not from the children, but from the adults who first step in. Aesthetics education comes after being moved. When teachers and parents are touched by beauty, children will also slowly draw near. Standing before a work of art, when we ask children, “What do you see?” we do not expect an immediate response. Instead, we give them space to imagine, allowing them to weave their own stories from the work. They do not need to “understand” the painting. Rather, it is a place that permits free expression, where they can say with boundless imagination, “I feel this painting looks like…” The art center exists precisely for such possibilities.

Children’s First Encounter with Art

Many believe abstract art is difficult to understand, especially for children, yet we often hear their surprisingly imaginative interpretations. In the first weeks after the art center’s opening this spring, several groups of teachers came for visits. Among them, Teacher Dabai, the art teacher at Taoyuan Elementary School in Taitung, always began by asking her students, “What do you see?” Each time she asked, it was like a key that opened the children’s eyes to viewing.

In front of On Wings of Song 25-00, a child said, “This painting feels like crying, because it has blue tears.” He noticed the dark pigments hidden beneath the vibrant colors, slowly flowing downward. Another child said it looked like a party.

Standing before the Untitled series, students from Rui Yuan Junior High in Luye, Taitung, shared, “The first piece is all dark, it feels very safe.” Another said, “There’s a person hiding beneath the deep colors.” From the scratches and brushstrokes, he read emotions that were not directly spoken.

In the third gallery, where sunlight streams down through triangular windows in the roof, a teenage girl thought, “It’s like when you feel that no one sees what you’re doing, but actually someone is watching, you just don’t hear them say it.”

What if a child says nothing at all? Teacher Dabai explained that it does not mean they have no feelings, but rather that they may still be searching for the right moment to speak. At such times, the only thing we can do is let them know that silence is understood, and words are permitted. Feelings will eventually be spoken at some point. She also shared, “The people that children are truly familiar with and able to trust are the teachers and parents who accompany them in daily life and learning. If a tour is led by unfamiliar staff, it may be harder for them to engage immediately.”

For children who are especially excited upon entering the gallery and find it difficult to stay orderly, having a familiar teacher guide them not only brings language closer to their understanding, but also better helps them form an emotional connection with the artwork.

Aesthetic Education Workshop: Education Comes After Being Moved

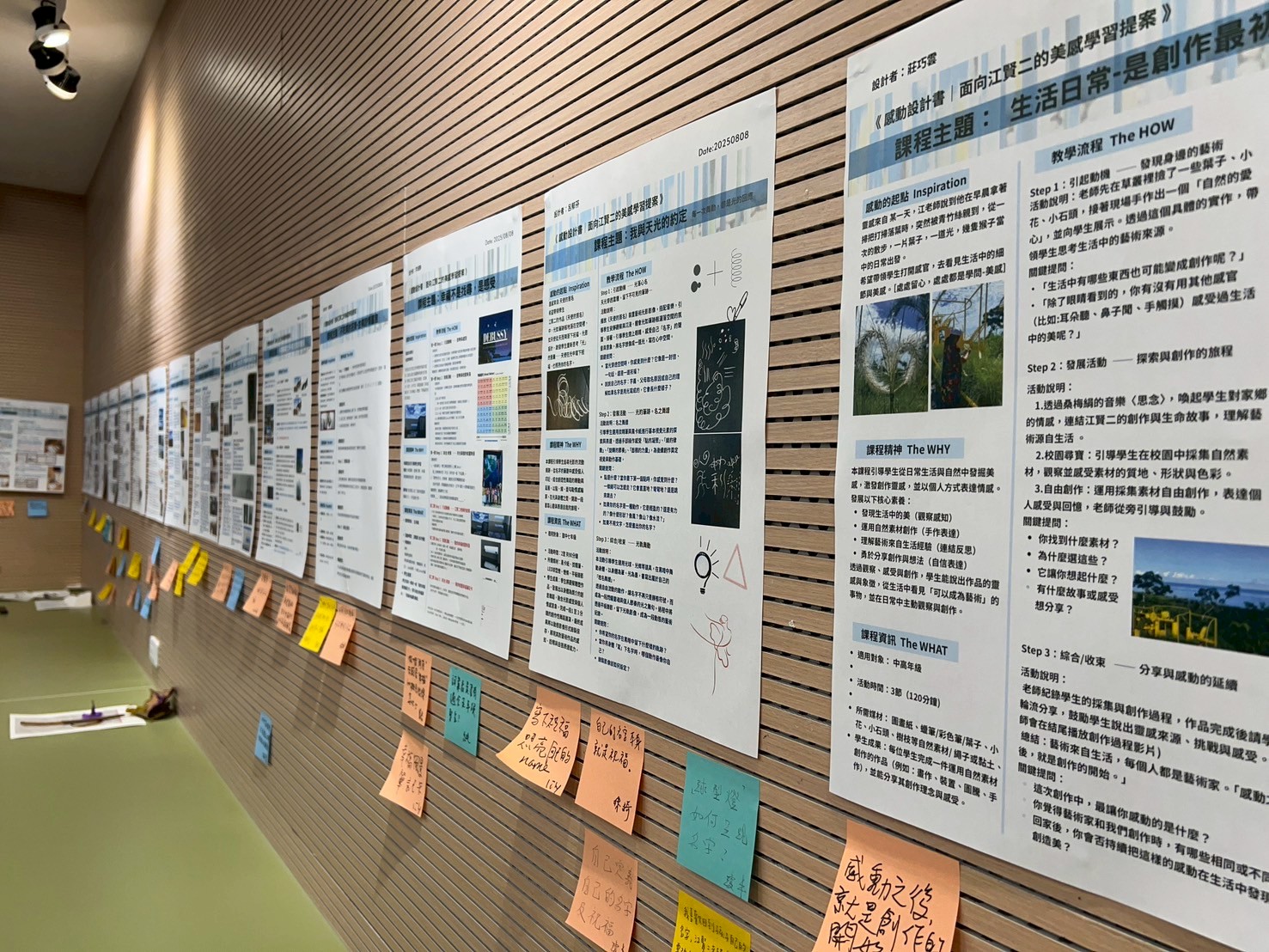

This summer, the art center held an aesthetic education workshop. Its creation was inspired by Teacher Dabai’s reminder and a simple reflection that if children’s feelings deserve respect, then educators’ feelings should also be reawakened. Therefore, the workshop did not begin with curricula, lesson plans, or learning objectives. Instead, it returned to a more fundamental question – when educators recharge and open themselves to feeling once again, will they then be able to truly lead children closer to art and beauty?

The program was co-curated by Jinna Sun, founder of the Taiwan Visual Arts Sharestart Educational Community (T-VAS) and visual arts teacher at Zhonghe Junior High School in New Taipei City, together with Fu Chun Lin, teacher at Long-Shan Elementary School in Taoyuan. The Paul Chiang Arts and Cultural Foundation invited sound-healing creator and handpan musician Myling Ho, contemporary artist Chien-yi Wu, and visual and performance artist and body movement guide Hai-Jung Sung to lead a series of sensory experience classes. Twenty teachers from both visual arts and non-arts fields, primarily from the Huatung region with a few from western Taiwan, spent four days, a total of 32 hours, in this workshop.

It was hard to imagine that the opening of a teacher training session would not begin with handouts or slides, but instead with bending down to touch plants and quietly listening to the sound of the wind flowing by. In the gallery after closing hours, teachers lay on the cool floor as Ho guided them to let sound slowly pass through their bodies, flowing like water. Even more unexpected scenes unfolded before Paul Chiang’s paintings, Sung invited everyone to extend their hands, starting from their palms, to sense the texture and rhythm of the works, allowing their bodies to gradually converse with the space. In just twenty minutes, teachers in different corners of the art center responded with an improvised dance to the rhythms and light they had felt.

The four-day program deliberately left ample open space, allowing exploration and reflection to become part of the learning process. Participants were in no rush to harvest answers; instead, they returned to their senses, touching upon those subtle perceptions that had been suppressed or forgotten in the fast-paced rhythm of daily teaching.

One teacher laughed and said, “I never knew I had a dancer’s talent!” Another remarked that it was the first time he had slowed down enough to see the curves of the mountains and hear the whispers of the wind. Though often facing the sea, it was only this time, through observing the Sound of Ocean and the Afternoon of the Faun series, that he truly noticed the flow of light and color within the space.

Designing Curriculum from the Children’s Perspective

The latter half of the workshop returned to classroom-based thinking. Using lesson plan templates and a “scaffolding” approach, the experiences were transformed into practical teaching designs. In her creative class, artist Wu introduced transparent sheets and collage materials, guiding teachers to develop flat images into three-dimensional structures. They explored the effects of overlapping color blocks and collages, then took the finished works outdoors into the sunlight, using the art center as the backdrop for observation which was an exercise that was both a creative experience and a teaching demonstration on space, color, and transformation.

The teachers began to reflect – where does the distance between children and art truly come from? In discussion, some noted that while today’s children are adept at handling screens, they have become less familiar with the tactile use of tools. Even small actions like using scissors or tearing tape feel less agile. Others observed that some children pursue perfection to such an extent that art class often becomes a source of pressure and frustration. These insights encouraged the teachers to experiment with lesson plan prototypes inspired by Chiang’s art, creating connections with children’s lived experiences and making closeness to art possible.

On the final day’s lesson plan presentations, one teacher thought of a student in her class who had undergone a frenectomy and was usually especially quiet in social interactions. She designed a course beginning with Chiang’s Debussy, combined with a picture book by Hervé Tullet, to guide children in viewing art while also practicing oral expression and muscle activity. Another teacher drew inspiration from Angel’s Signature 24-00 in the third gallery, leading students first to recognize their own names, then using ribbons and dance to “paint” the traces of light belonging to their names. Yet another teacher began with Chiang’s Self-Portrait, guiding students to depict their inner selves and practice identifying and expressing feelings.

These lesson plans were not merely procedural steps, but rather starting points for understanding the world, tailored to the Huatung children’s everyday encounters with the sea and nature. At the close of the workshop, one teacher remarked, “Having a space like this in Taitung, where we can experiment and draw near to art, is a truly rare and precious thing.”

Growth of the Interns

This summer, three high school students from Junyi School of Innovation in Taitung also came to the art center for a one-month internship. They read Chiang’s autobiography, practiced oral expression, participated in gallery maintenance, learned tour-guiding techniques, and accumulated their own observations and experiences through interactions with visitors.

Intern Pin-Yen recalled that her previous experiences visiting art museums left her feeling that they were “sacred and untouchable.” Yet the art center’s open environment, with its interaction with nature, felt warm and approachable, breaking her impression of museums as overly solemn. Tian-En, who studies “Contemporary Art” within Junyi’s three innovative subjects and also loves music, shared, “Every day I immersed myself in Mr. Chiang’s works. I could sense how he listened to music while creating his art.”

To prepare for tours, the interns took extensive notes and often quietly listened to the explanations of other volunteer docents while working in the gallery. Yu-Ying shared, “I would practice the day before my tour and even time myself, so that I could get the pacing right.” She discovered that when actually stepping into the guide role, the most important part was simply the beginning; the content she had prepared was already in her body, and once she opened her mouth, everything flowed naturally.

Within just one month, the once-shy interns transformed from introverts to extroverts. Their interactions spanned from children whose height barely reached their knees to visitors from countries such as the U.S., France, Germany, Japan, and South Korea. From initially shying away from foreigners, they grew into practicing natural exchanges, and by asking questions and listening, they sought advice from experts in various fields. For example, Yu-Ying, who chose “Green Architecture” as her innovative focus subject at school, gained new insights into the beauty of the art center’s fair-faced concrete design through the perspective of a visitor with an architecture background.

Aesthetic Sensibility Is Not Boxed In, but Cultivated

Three years ago, a young mother carrying her one-month-old baby walked into the Paul Chiang Art Center, which at the time was only partially open. Looking at the tiny sleeping life, Chiang said to the mother, “Bring him back when the art center officially opens, and we will celebrate his birthday!” That heartfelt invitation was like sowing a seed of hope in the wind, not only for one child, but for an entire generation; not only for one mother, but also as a promise of what this art center is meant to become.

The art center seeks to return learning to the scale of the land. Aesthetic sensibility is not boxed-in knowledge, but a capacity that can be cultivated. As children let their eyes wander between artworks and shifting light, move between colors and emotions, what they learn is not just how to look, but how to feel themselves. From the dialogue between teachers and students, to the budding of lesson plans in the workshop; from the guiding experiences of interns, to the genuine responses of visitors, aesthetic education does not necessarily require facilities, nor must it wait for a complete system. It can begin from a single sentence, a simple intention made for the sake of children and slowly grow into a form unique to this land.

To the mother who visited in 2022 with her one-month-old baby – If you ever have the chance to return to the art center, please contact us! We would love to say hello.

When Accompanying Children into the Paul Chiang Art Center, You Can Begin with These Three Simple Questions:

- What do you see?

- How does it make you feel?

- If you were to give this artwork a title, what would it be?